Chinese Fox Spirits: A Brief Introduction

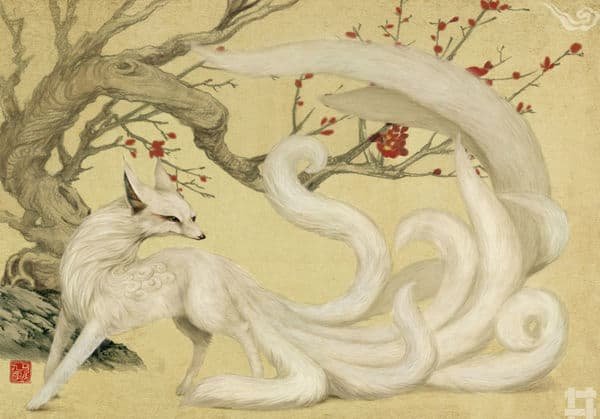

The fox spirit is an image immortalised in numerous fictional depictions, especially in Asian tales, contemporary or traditional. This is no surprise, considering their prowess over glamour, enchantment, and the seductive qualities for which they are notorious. However, such depictions barely scratch the surface of what these spirits are capable of, their magical and cultural significance regarding the roles they have played throughout history, and the nature of their worship as practised in bedrooms, backrooms, and temples alike. Today I would like to provide a very brief introduction to these spirits and the role they play within my specific cultural context, digging into the very rich historical background of these beings that lurk beyond their fictional counterparts.

Foxes, like several other animals in Chinese tradition, were believed to possess the ability to cultivate and siphon energy from the sun and moon. This would allow them to prolong their lives and eventually transcend their animal forms, and had to be practised regularly over several centuries. Eventually, these spirits would be able to shapeshift into a human form, at which stage they also acquired great magical knowledge and power, becoming shamans, healers, poisoners, sorcerers, mediums, and diviners. Over time, they even gain the ability to become celestial beings, equivalent to minor gods and goddesses, earning their entrance and place into heaven. This final stage is not without its sacrifices or struggles, as often in stories, these spirits form bonds with humans that they are required to give up in order to complete their transformations. I was also told by my family that this process involves not just the cultivation of energy, but hinges on their steady performance of good deeds in tandem to this in order to build the karmic merit required for such transformations. This concept makes sense when you consider the Chinese belief system of reincarnation: what you reincarnate as is entirely dependent on the life you lived, and animals hoping to reincarnate as humans will have had to build up a significant quantity of good deeds to do so. As fox spirits are essentially seeking to be able to achieve and later transcend a human state temporarily semi-permanently, without the process of first dying, it makes sense that this is a keystone of such rites.

The worship of fox spirits remained largely a folk and familial practice, limited to private quarters and worship, as opposed to being enshrined openly in public temples (although a few kept smaller backrooms dedicated to various huxian, or had smaller, more informal temples opened in dedication to a fox spirit). And unlike the worship of most gods and spirits which took place in public temples, the huxian was often consulted in more private and familial matters or fertility, sexuality, and the inner workings of marriage or familial dynamics. They could also be called on for matters of wealth or honour, especially when it came to the restoration of such things, such as family reputation or wealth that had tarnished. They could also be petitioned to provide healing or consulted as diviners to shed light on spiritual matters or the future. In myth and folklore there are stories of huxian intervening personally and directly, however in folk accounts such encounters are rarer, and usually only occur if there is already a familial or ancestral link to a particular fox spirit, or if for whatever reason that individual happened to catch the eye of such a spirit. Otherwise, all encounters happened through a medium chosen and pacted to a particular fox spirit. And for those who romanticise such arrangements, I would include a note of caution as mediumship to a fox spirit is often portrayed as a double-edged sword. While it can bring advantages (usually financial) to the family of the chosen medium, it forever alters the life of the one chosen, making it difficult if not outright impossible to continue with regular life, interests and the fulfilling of ordinary jobs or roles within the community. It is also rarely something that the medium chooses out of their own free will: it was actually a common fear for most to be selected, and more often than not the methods employed by the spirit to convince the medium to consent to accepting the role involved afflicting them with hallucinations, involuntary possession, and illness until they have no other choice but to consent. They are then often met with disdain and scorn by the townsfolk they encounter and serve. Fox spirits received a mixed response, but even in circumstances where the spirit was respected, their mediums were usually not offered the same level pf deference, and were often shunned and excluded from society. This of course excludes the challenges posed through various rules spirits gave their mediums as well which could also make life very difficult. I mention this as there is often a tendency to glamourise such roles, and while positive accounts do exist of mediums and their spirits, it is important to emphasize the difficulty associated with the position—even when such relationships came with boons, the role of medium was not something to desire, and it came with a lot of stigmas and challenges, both imposed by the spirit and the community, that would be too complicated to explore within this article fully.

Here is a good point to note that worship of or work with fox spirits is often considered taboo, and for good reason. While these beings could be extremely beneficial, they were also considered capricious and dangerous in several capacities. Numerous stories of course document the succubus-like nature these spirits can have, often seducing men and feeding on their energy until he wastes away, becoming weaker and riddled with illness before death finally claims him. Others in a similar vein indicate a sadistic quality to some of these seductions, where fox spirits bewitch their paramour so thoroughly that they are led into situations of pain, danger or madness for the fox’s amusement. Seduction aside, the danger of these spirits also lie in their great power: cautionary tales mention illusions so strong that the victims are drawn deeper and deeper into deception after deception, or are afflicted with a litany of illnesses and madness, and/or suffer from a loss of luck, wealth, and honour. The hand that blesses can also curse, and this cannot be made clearer than in these tales that present the counterpoint to all the stories of blessings, as these spirits possess such thorough mastery over their areas of expertise that they can just as easily destroy (or bestow the opposite of) what they can bring. Some of them are even shown to be extremely resistant to exorcism or banishing, and often play with the priests that are called upon to perform such rites with their shapeshifting and illusions. Stories exist of priests attempting to banish fox spirits, only for that spirit to either pretend to have been subdued, or to shapeshift into the form of a superior or god worshipped by the priest in order to trick them and toy with them. It is even noted that gods and larger spirits responsible for reining in spirits and preventing them from interfering too heavily in the lives of mortals will be reluctant to kill or deal out heavy punishments for these spirits, due to the level of discipline they demonstrate with so many centuries of cultivation and study necessary to achieve their power (which is not to say that they will not intervene, but one cannot rely too heavily on them to provide a permanent solution to those being plagued by an angry, hungry or sadistic fox). This reputation is what leads to the (warranted) disclaimers that come with approaching these spirits, and explains to some degree why their worship never quite made it out of folk practices. It is also why I would caution anyone seeking to approach them to proceed with care: depending on the nature of the fox you approach and the manner of your approach, you may get more than you bargained for and once offended (or even successfully contacted, in some cases), they are not easily appeased or banished.

The choice of a fox spirit to engage with and aid in the problems of humans in such a manner is often speculated on, and I believe that while of course, each spirit has its own motivations, some common ones exist. The first is simple interest and care for humans, which can be demonstrated in numerous myths of huxian becoming fascinated with humans, sometimes to the point of attempting assimilation and thus ceasing their search to ascend fully to godhood. Often in these cases, the circumstances are romantic, however, occasionally the fox chooses to pursue a more familial route. The second reason is that performing such services to a community is one of the necessary stepping stones to their ascension, as previously mentioned they need to fulfil a number of ‘good deeds’ in order to do so.

Today fox worship is largely relegated to smaller temples or the living rooms of practising mediums, and is either obscure, thought of as the work of fiction, or mentioned in whispers as something taboo and dangerous. In short, little has changed, only that debates about their merits also include whether one is over-enamoured with their fictional depictions. However, many actresses and celebrities in East Asia have confessed to worship of fox spirits, and that connection is hardly surprising, given their noted historical patronage of artists—they are thought to be particularly fond of (and many have been credited to be the inspiration of) poetry, music and dance—and their abilities over seduction and glamour. As I may have mentioned in previous posts online, I myself work within the performing arts, and would not be surprised if my success and even interest in this field have something to do with the fox spirit to whom I am pacted, as while I did not know this until I began to work with her properly a few years ago, she has been with me since childhood and made her presence known at several points of my life through various signs, blessings and omens that I did not fully recognise until recently. These spirits are very close to my heart, and while we have barely scratched the surface of their lore or the magic with which they are associated, I wanted to be able to provide a bit of a primer acknowledging their significance as a sort of tribute to them. I also have no doubt that I will be expanding upon this topic in future, as there are definitely elements of them that I would like to explore in more detail.

Shades of Life and Death: Fairies and Colour Symbolism

There is power in colour, this much we know—we have long employed them to denote virtues, qualities, status and a myriad of other information about the individuals that adorn themselves with it in all areas of life. They have become a visual language weaving together clues about allegiances and provenance, and in magic, they can be used to draw upon the power, protection, or malice of the powers to which they are tied—for those who know where and what to look for, and when to employ them.

Today our exploration centres specifically upon the symbolism and potential uses of the shades associated with fairies (and fairy-adjacent creatures). Now, it is not uncommon for specific colours (primarily green, red or white) to be indicators of a fairy nature when worn or otherwise displayed: spirits in folk tales or songs that are clothed in green or red are often revealed (or understood) to be one of the Fair Folk, and a similarly damning combination is that of white and red—from white cows possessing red ears to the pale-skinned redheads that are often a sign of the fae-touched. Confirmation came especially to those presenting a combination of the three—a green shirt, a red cap, a white owl’s feather, for instance—and I wonder if, beyond the simple fact that an excess of signs makes it more obvious, the reason these colours are often presented together is that they exist as shades and facets that fit together to form a more cohesive whole.

“The Meeting of Oberon and Titania”, illustration by Arthur Rackham

The specific mention of these colours is not only a device that communicates in a succinct fashion the natures of these beings, but when appearing in day-to-day accounts or encounters, they served as a warning to those unfortunate enough to stumble upon them or those seeking to wear the shade. The latter, of course, is thought to be seen as an invitation for their attention, provoking potential jealousy, outrage and mischief. However, these colours are on occasion used as a ward—sparing those wearing the shade from harm at the hands of the Folk. An account from Islay details the story of a pair of siblings that were walking past a loch when a fairy man ran past and touched the boy, blighting him with life-long paralysis. His sister, on the other hand, who was dressed in green, was left alone and uninjured (Briggs, 1961). This is an unusual account where green is thought of not as a dangerous colour that would bring malice from the fairies, but as protection in its own right, and I cannot help but wonder if it is because the fairies are so fond of wearing it themselves that this was interpreted as a declaration of allegiance as one of Theirs.

“And there he saw a lady bright,

Come riding down by Eildon Tree.

Her shirt was o the grass-green silk,

Her mantle o the velvet fyne.”

— Thomas the Rhymer

The fairies’ fondness for green is famed, from the Queen of Elphame to fairy ladies and men depicted in the shade, and out of all the colours we could mention today, it is perhaps the most well known as being Theirs. There existed such a strong connection that green objects were sometimes intentionally called blue instead, for fear that simply saying its name would call up the fairies (Goodrich-Freer, 1899)—for as we know, there is power in names. Green was thought to be the colour of death in Celtic culture (Hutchings, 1997) which is not too surprising, given the connection between the fairies and the dead, and yet there is far more that lurks beneath the verdant surface. For green is the colour of the bountiful forest—the full might and force of nature left to flourish and consume; the creative power of life itself. It is also that of decay—when the earth comes back to claim that which has always been hers; when moss and algae take root upon that which once had a life of its own. It is the encompassing cycle of life: life to death and life from death, again and again in a fluid circle dance. It is never-ending youth and life, the kind that will never die as it is always reborn; it is poisonous jealousy; it is the patient march of time, unchanging despite the winds that blow and the cracks that appear in stone. It is that which rises to fill those cracks, between stone and road and monument. It is Elphame—betwixt and between, ever-present and waiting, patient in its claiming. It is what has ever been, and ever will be.

Red, although slightly less synonymous with the fairies as green, is mentioned nearly as often. It appears more in accounts of the fairy folk who are more bloodthirsty, like the redcaps who dye their hats and clothes in human blood. Now, blood is violence and strife and death, which is worth caution, but it is also life, for it nurtures and nourishes us from womb to tomb. The feelings that make us most alive are often associated with red—passion, love and desire—these things that light us up and make our hearts race in a reminder that we still live. It flows through our veins as it flows through the rivers of Elphame: a constant stream that threads us with vitality. How especially fitting this is when we consider the Pale Ones and their famed (and often dangerous) sexuality, often mentioned alongside their love of violence and merriment. Red is also fire—the warmth in the hearth and the bonfire that bears witness to raucous merriment; it is a torch piercing the dark night to illuminate the treacherous woods. It is the fire of magic, and this is fitting when you consider the close ties fairies have to witches in folklore. The Queen of the Fairies is also a Witch Queen, and in her hands is cradled the witches’ flame, hers to bestow and to take and to wield. When she appears in red, as witches have sometimes claimed to see, more often than not this is the mantle she takes: our Lady of the Sabbat, our Lady of the flames, our Lady of love and life and death, our Mother of Witches.

A less complementary perspective on explaining the fairies’ connection to the colour red comes from a quote from the legend of Saint Collen and the Fairy King, in which the Celtic saint claims that fairy pages wear “blue for the eternal cold and red for the flames of hell” (Briggs, 1976). The connection between hell and the Folk is well-documented: They’re known in some legends to pay a tithe to hell, and some theories regarding the origins of the fairies suggest that They are fallen angels. The mention of blue here is interesting, not just for its reference to the cold, for certain fairies (especially the Queen of Elphame) is thought to be associated with the colder and darker months of the year, but because blue is also representative of water and the ocean, which was often thought of as a gateway to the fairy realm. It is also, notably, both the fount of life and a source of death: holding within its watery depths a similar quality to blood (for are blood and water not the rivers from which life flows?) while also possessing the quality of a conduit between the mundane world and Theirs.

White is at once the most obvious and the most nebulous. The fairies are called the Fair Folk, the Pale Ones, the White People, and the Shining Ones for a reason—it is no surprise that their bleached pallor lends itself to clothing as well. And white is the colour of the dead—when life is leached from the skin; when blood ceases to pulse; when bones are picked clean and bleached by hand or sun. It is the colour of life gleaming bright and full of possibility, a blank page upon which to be written. White is the very quality of liminality: holding within itself limitless possibility, at once there and not, containing every shade and appearing to hold nothing at all. It shifts and shimmers like fairy glamour, waiting to be coloured by perception, idealisation—waiting to be written over. It is also the colour of the luminous moon, observant and unblinking in the night. The Queen of Elphame (and the fae themselves) possesses a great many lunar qualities and is also sometimes called the Lady in White. In this aspect, she is the queen of the shades and the unseen arts, teaching us to tend to the dead, to weave fate and to see the past, present and future. Here she is Diana, riding by moonlight at the head of the Wild Hunt, her entourage of ghostly shades pale and shining behind her.

While it is not mentioned often as a colour associated with the Good People specifically, it does on occasion appear in depictions of the Queen of Elphame, and thus I would like to make mention of black as the twin and converse of white, again holding at once everything and nothing, but it exists as the shadow cast by light—two halves of a whole. And indeed, in most cases where She appears in black, it is often noted how pale white her skin or hair is in contrast. Black is for womb and tomb, as the rhyme goes: it is the colour of the deep night, of the fertile soil, which envelops and births and breaks us down again. It is both the exacting blade of death and the tender earth cradling what is left, guiding it onwards to a new life. It is the solemn silence of sleep and death, those times when the soul slips out of the body to dance with the spirits. Let us not forget that the Fair Folk are fond of oneiric communication as much as they are thought to hold the souls of the dead in their company, and as much as they are thought to be rulers of those secret things that dwell in the shadows, betwixt and between the sun and moon and trees.

All of these shades present some sort of duality—between life and death, beauty and ugliness, a double-edged sword that dazzles and blinds with the flash of its blade—and how fitting this is when we consider the very natures of the Other Crowd. Colour aside, this duality is often on display in physical descriptions of them—it is often noted that even in the forms they take that are designed for seduction, there are usually clues that give away their fairy nature. Be it a beautiful woman whose back is as hollow as a seashell, a handsome young man whose hems are always wet, or a mysterious stranger so lovely you don’t notice their hands or feet face backwards until it is much too late. This may arguably be a sly warning—a test—or a mistake or oversight in their glamour, but perhaps it is more a reflection of their liminal nature: at once civilisation’s ideal and the horrific wilderness. This dance of life and death is something that can be applied to the rest of the colours associated with the fairies, but it is interesting how each presents additional subtleties.

WORKS REFERENCED / FURTHER READING:

Folklore and Symbolism of Green by John Hutchings

Some Late Accounts of the Fairies by Katharine Briggs

An Encyclopedia of Fairies by Katharine Briggs

Fairies and the (Restless) Dead

(This is a repost, the original was first published on Blood and Hawthorn when I was a writer there.)

The land of Elphame and the classification of its denizens is something of a mysterious subject, but as December wraps us in her cold embrace and the Wild Hunt tears through our skies, let us explore a sliver of the thread running through folklore and mythology that ties some of the spirits we call fairies and the spirits of human dead together.

“The Fairy Rade: Carrying off A Changeling” by Sir Joseph Noel Paton

In Celtic folklore, the realm of the fairies was often thought to be, if not synonymous, at least overlapping to some extent with that of the human afterlife. The mounds within which the fairies dwelt were sacred not just because they belonged to the Folk, but also because they were thought to house the souls of the human dead awaiting reunion with their bodies on Judgement Day (Kirk, 1893). The notion that the dead reside with the fairies as a sort of interim between life and their proper afterlife depicts Elphame and the very nature of being faerie as a sort of purgatory, a state between all realms—living and dead, heaven and hell. It is to be on earth but not entirely upon it as the living are, nor entirely apart as those dwelling in heaven or hell are. It seems to be a state of waiting, of being betwixt and between, neither entirely here nor there.

This idea of Faerie as a sort of purgatory can be supported by the existence of spirits like the Tarans or Spunkies of Scotland, who were assumed to be the souls of babies who died before being baptised that were frequently sighted lamenting their fates in the woods. (Briggs, 1978) Pixies and Piskies were thought to have similar origins as well, being either unbaptised children or the souls of pagans that died before Christianity took hold in the British Isles, and thus “were not fit for Heaven but not bad enough for Hell” (Briggs, 1978), which is a sentiment often echoed in most tales describing the fairies and their origins. Now, that is not to say that all these spirits are necessarily one and the same with the fairies, but as Briggs puts it, “they yet have so much in common that they belong to the same genus”. Yet maybe it is a matter of allegiance that causes these spirits to band together as such: the lack of a prior claim on the souls of these unbaptised spirits may be what allows them to accompany the fairies so (and taking on various behaviors and classifications as a result). Or, if one is to ascribe to the theory that the fairies are the ancient gods that were ousted at the arrival of Christianity, it makes sense that they would be accompanied by the spirits of their followers. After all, folklore is based upon the observations and beliefs of humans, often without much context of what might have passed between the spirits before these sightings or experiences, and the negotiations, bargains, or reasons these spirits may have between themselves is likely to be varied, nuanced, and ultimately not for most to know.

There also exists within accounts of humans encountering faeries the theme of recognising the spirits of the dead in the service or company of the Fair Folk. In the ballad of Sir Orfeo, when Orfeo journeys into the kingdom of the fairies to retrieve his bride from Finvarra, king of the fairies and the dead, he recognises within this world the figures of dead men, all of whom appear to have died before their time for they bear mortal wounds: headlessness, missing limbs or marks of strangulation. In addition, there is a story in Lady Wilde’s Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland, wherein a man travelling on November’s Eve finds himself caught up in a fairy fair and recognises amongst their company the faces of friends and villagers who had died.

And when Hugh looked he saw a girl that had died the year before, then another and another of his friends that he knew had died long ago; and then he saw that all the dancers, men, women, and girls, were the dead in their long, white shrouds.

Lady Wilde. “Ancient legends, Mystic Charms & Superstitions of Ireland”

The witch trials in Scotland present a theme of witches having familiar spirits that were associated with Elphame (if not thought to be fairies themselves) that once were human dead. Alison Pearson, for instance, claimed that several deceased members of her family now resided in Elphame; Andro Man spoke of knowing several human dead in their company, one of whom was the late King James IV, who had been killed at the Battle of Flodden. Elspeth Reoch had a similar arrangement with a relative called John Stewart, who had been murdered (Kruse, 2021), and Bessie Dunlop made mention in her confession of a spirit named Thomas Reid, a former officer who had been killed in battle. She also recognised the Laird of Auchinskeith—who had been deceased for nine years at the time of the sighting—travelling with the fairies. Note that the mentions of the dead in the realm of the fairies or in their company are often noted to have died violent deaths: significant perhaps because of their violent nature, or because dying in such a fashion was thought to be premature.

The importance of such deaths might be seen more clearly by examining the fate of the Bean-Nighe —the spirit of a woman who died in childbirth—usually thought to be a fairy or at the very least, something fairy-adjacent. She is most often sighted beside quiet bodies of water, washing and beating the clothes of those soon to die; her presence is usually interpreted as a sign that death is near. Like certain fairies, who are noted to occasionally have exaggerated and unusual features, she is noted to possess extremely long breasts, and sometimes to be short as a child and is sometimes dressed in green (the colour of the fairies). Her state was thought to be a result of the circumstances of her death:

Women dying in childbed were looked upon as dying prematurely, and it was believed that unless all the clothes left by them were washed they would have to wash them themselves till the natural period of their death.

John Gregorson Campbell. “Superstitions of the Highlands & Islands of Scotland”

This concept of being stuck in this purgatorial state because of premature death may explain not just her fate and those above, but it also sheds light on the circumstances that might result in a spirit gaining more of a fairy nature: the presence of a liminal factor during death. Female spirits becoming notable restless spirits is a theme echoed in cultures around the world, and I wonder if it is the liminal nature of such deaths that results in this—the process of giving birth places both mother and child in a sort of liminal state, and perhaps it is death during this that contributes to their altered state.

Other spirits falling under this umbrella of fairies that were thought to have originated from spirits that could be classified as the restless dead include the Sluagh of Scotland. They were to be “the most formidable of the Highland fairy people” (Briggs, 1978) and were perceived as comprising of the spirits of the evil, or unforgiven dead. They were known to fly through the skies, haunting the sites of their crimes on earth and fighting battles against one another. They were famed for killing animals with the use of darts that never missed, and for enslaving mortal men to their will. Like the other spirits we have already mentioned, the Sluagh are thought to be in a form of purgatory, unable to ascend to heaven until their transgressions have been atoned for. (Briggs, 1978) Unlike some of the other spirits we have examined, however, the condition that has to be met in order to release these spirits from this purgatory appears to be far more attainable, and yet their predisposition and enjoyment of violence prevent this. It is a separate sort of purgatory: not so much born out of being caught between life and death or stuck in a position where death has claimed one early, but out of dying with ties strong enough to tether them to this plane enough that they cannot move on without its resolution.

Obviously, death is the main catalyst for this metamorphosis that enables the transformation into beings closer to those we call fairies, perhaps because it removes the obstacles that hinder easier access to our powers: similar to the spirit death that transforms and creates witches. Not unlike spiritual death, for this transformation to be complete, it would appear that specific conditions must be met. In most cases, that seems to be a lack of completion in one’s lifetime, whether that is caused by an early and violent death or some religious or personal circumstance (which also happen to be a hallmark of the restless dead). The idea of fairies being an unfettered version of the human soul is likewise explored by Kirk, who suggests that “the small size of the fairies might be plausibly accounted for by the primitive idea of the soul as a miniature replica of the man himself, which emerged from the owner's mouth in sleep or unconsciousness. If its return was prevented, the man died.” Yet, it is interesting to note that most of these tales make mention of the majority of the human dead often either in service to the Good People, or merely as dancers and revelers in their company. It seems that death alone is enough to allow human souls to partake in the revels or journey in the company of the Folk, to serve as their messengers or dwell in their hills, enough that a broad generalization could lump them in that classification, but it does not necessarily make these spirits truly ‘Faerie’. For that, it appears that intervention on behalf of the Folk themselves is required.

It is entirely possible, of course, that the majority of the human dead and the fairies are merely spirits that overlap and are adjacent or similar enough to share time and space, barring a few exceptions. The circumstances of death and the life lived by the individual as well may determine commonality and shared interests that further allow for this compatibility, and the sightings that occur while these spirits are together engaging in their various activities. Walter Evans-Wentz explores this in The Fairy Faith of Celtic Countries:

Fairyland is a state or condition, realm or place, very much like, if not the same as, that wherein civilized and uncivilized men alike place the souls of the dead, in company with other invisible beings such as gods, daemons, and all sorts of good and bad spirits. Not only do both educated and uneducated Celtic seers so conceive Fairyland, but they go much further, and say that Fairyland actually exists as an invisible world within which the visible world is immersed like an island in an unexplored ocean, and that it is peopled by more species of living beings than this world, because incomparably more vast and varied in its possibilities.

Walter Evans-Wentz. "The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries"

Fairyland in this description encompasses all of the Otherworld, essentially housing spirits of all categorisations; a sentiment that seems well supported in various accounts of the fairies and their company, but the theories of their origins which encompass not just the dead, but also fallen angels, ancient gods, and old spirits. All of whom, of course, are often thought of in relation to the fairies as well. The origins of the fairy folk are widely ruminated upon: from ancient gods to fallen angels, the shades of human souls, or something that is all and neither of the above. The Folk are complicated, and I doubt that there will ever be a single theory or classification that manages to encompass and hold true to all of The Good People. They tend to, by nature and by will, defy categorisation, so I will leave you with a reminder that it is never prudent to jump to any conclusions or apply generalizations when it comes to Them. That said, I hope my little foray into some of the folklore available on this subject made for an interesting read.

WORKS CITED / FURTHER READING:

An Encyclopedia of Fairies by Katharine Briggs

Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms & Superstitions of Ireland by Lady Wilde

Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland by John Gregerson Campbell

The Darker Side of Faery by John Kruse

The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries by Walter Evans-Wentz

The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies by Robert Kirk

Ian. (2018, November 28). Bessie Dunlop, the witch of Dalry. Retrieved from https://www.mysteriousbritain.co.uk/folklore/bessie-dunlop-the-witch-of-dalry/

The Significance of Names: A Brief Exploration

(This is a repost, the original was first published on Blood and Hawthorn when I was a writer there.)

The topic of names is something that has been on my mind for quite some time, and it seemed fitting that with the launch of this new blog, I’d write about and explore that which is customarily associated with births and new beginnings. Cultures around the world will attest to the fact that names are not only essential out of practicality, but also deeply influential on the future of a child. They are wards and wishes, blessings and protections, but in fairy faith, magic and witchcraft, they can also be weapons wielded against you—give the wrong spirit or witch your name, and be prepared for all manner of malice, mischief and misfortune to be unleashed upon you. After all, one of the most renowned pieces of folklore surrounding the Good Folk is that you should never give them your name. But what specifically is it about names that make them so important?

The most obvious answer, of course, is that they are what you are identified by. Names, in essence, are a summation of your identity and personality, and often reflect pre-existing circumstances—betraying occupations and regions from which they originate. But they are also definitions: to name something is to define them, to grant it purpose and meaning. It is why we name tools, emotions, children, spirits—to bestow upon them our hopes and intentions for their purpose, to create an identity they can grow into and fulfil. This, of course, strengthens with the choice to continue using it as a representation of yourself, both in your eyes and that of others.

In Chinese folklore, names are believed to be tied to fate, as it is believed that a child’s name will shape and determine how the rest of their life will play out. As such, great care is taken before a name is determined, and elements including but not limited to the meaning of the name in question will be thoroughly considered. It is not uncommon for parents to consult experts in Feng Shui or religious leaders and diviners before choosing a name for their child. This often takes the form of consulting Bazi charts to analyse the conditions of a child’s birth and how it will grow to affect their lives and personalities, then selecting names to balance out any deficiencies in any elements found in those charts. My name, for instance, was primarily intended to balance out a deficiency of water in my chart. That said, it is also believed that a name can grow inauspicious with time, and there are numerous stories of those struggling with issues regarding their health, finances or romance who change their names and experience a drastic reversal of fortune as a result. This addresses the question of significance, while also providing some ideas for those of you who are magically inclined: the warping or changing of an existing name for a target could be used to reverse, harm or heal.

In a similar vein, some cultures choose names for their children that mean ugly, sick, or unremarkable, as this is believed to thwart spirits that might steal them by convincing them that these children are just that. This suggests that the names we choose might be just as important or even equivalent—to spirits if not to other humans—as our own natures.

Then, of course, there are the names, or more specifically, titles, epithets, or descriptors one may use in lieu of a name. This comes in more specifically with the names given by certain deities and spirits, namely the Fair Folk, who are notoriously loath to part with their true names. These can either be derived from historical or folkloric sources, obtained directly from spirits, or fashioned yourself from your observations and interactions with a spirit or deity. While perhaps not adhering to our expectations of what a name is, these can be comparably significant as they still contain information and power, being that which these spirits are and can be called by. In addition, it could be extremely revelatory—providing clues as to the nature of the spirit, the aspect of themselves they wish for you to work with, and the form of relationship they wish to take with you. Similarly, if it is an epithet you have fashioned for them, it can serve both as an offering of praise or a tool with which to share your perspective and intentions for the relationship. It is not an unwise habit to utilise these, as it encourages specificity that can ensure you are, in fact, reaching the spirits that you intend to call upon, while also assisting in strengthening your bonds with them. To that effect, calling upon deities using epithets can strengthen your prayers, invocations and workings with them, both as an exploration of their depth and power, and as a clarification in prayers or magic that allow them to know which aspect of theirs you are calling upon—and what sort of help you are seeking—in any given setting. In the context of Hellenic polytheism, for example, to call upon Aphrodite Areia would be to invoke Aphrodite’s warlike aspect, which would make sense in prayers to her to aid you in seeking justice, whereas to invoke her as Aphrodite Pandemos would serve you better in matters of sensual pleasure.

The numerous epithets, euphemisms, and names people have given to the fae over the years expand on this, while also providing an example of names as a vessel of hope: they are names that seek to flatter or remind the Folk of their better natures to avoid drawing their ire. There is an example of this in an old poem:

"Gin ye ca' me imp or elf

I rede ye look weel to yourself;

Gin ye call me fairy

I'll work ye muckle tarrie;

Gind guid neibour ye ca' me

Then guid neibour I will be;

But gin ye ca' me seelie wicht

I'll be your freend baith day and night."— transcribed by Robert Chambers, from ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’

(“If you call me imp or elf

I advise you look well to yourself;

If you call me fairy

I’ll work you great misery;

If good neighbour you call me

Then good neighbour I will be;

But if you call me blessed sprite,

I’ll be your friend both day and night.”)

Here, the advice imparted is that to call one of the Folk by a name that is either unflattering or reflective of their more mischievous nature would be to invite their mischief or malice, and to utilise a name that calls upon or reminds them of their better nature would be to enjoy better company. It suggests and reaffirms my previous point that the names you choose to invoke your gods and spirits by can determine the aspects of them that answer.

The significance of names boils down to this: they are a summary of who you are, what you consider yourself to be, and everything else laid out in front of you. They are the essence of your identity: what is, what has been, and what will be, and all the hopes and wishes tied to that. They are what you answer to, what has been chosen for you and what you have chosen. They are what you are known by. So guard, choose, and examine your names well, for within those simple syllables hold the key to you: your past, your present, and your future.